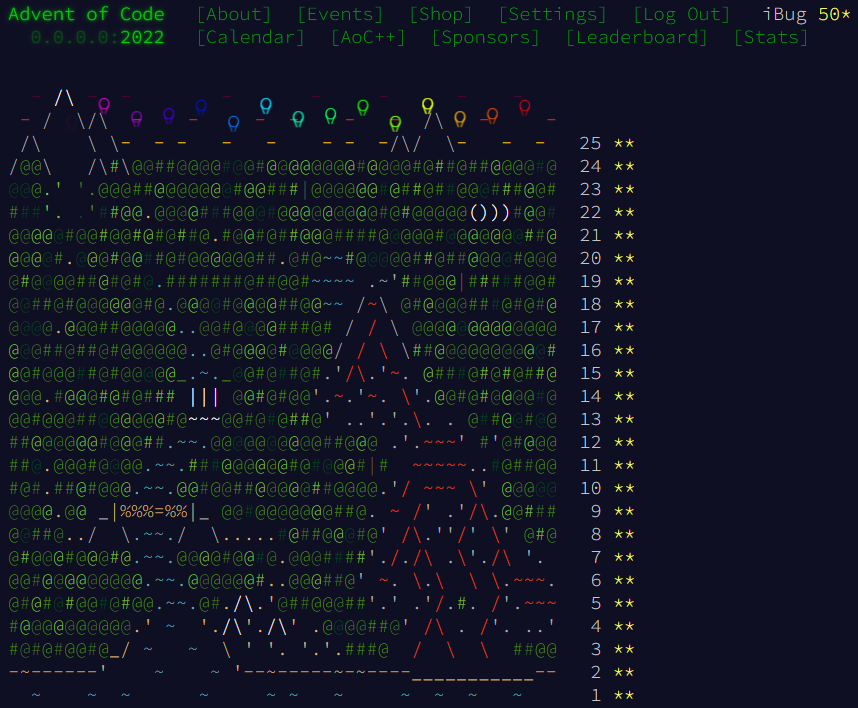

Advent of Code (Wikipedia, link) is an annual event that releases a programming puzzle every day from December 1 to December 25. It’s a great chance to learn a new language or practice your skills.

Considering that all the puzzles are designed to be lightweight, meaning that if implemented correctly, they’re solvable in no more than a few seconds with a reasonably small memory footprint, I picked Go as my language of choice. Go has been my preference over Python for a while, for being compiled into machine code and thus more performant, and a decent set of standard libraries.

Notes on puzzles

The first 10 puzzles are very easy and doesn’t even require special knowledge. They’re practically just text processing and simulation, so there aren’t many comments to be made.

-

Day 2: While it’s straightforward to implement a rock-paper-scissors game using

switches or lookup tables, noticing that shapei+1beats shapeiallows us to simplify the code in an obscure way.For example, I implemented the “shape score” as

int(s[2] - 'W'), and the “outcome score” as(4 + int(s[2]-'X') - int(s[0]-'A')) % 3 * 3for the first part. For the second part, the “shape score” is now1 + (int(s[0]-'A')+int(s[2]-'X')+2)%3, and the “outcome score” isint(s[2]-'X') * 3.This is certainly not the most readable code, but it’s a good example of how to use math to simplify code. Less code = less bugs, and if you’re really crazy about that, you can always add unit tests to ensure that the code doesn’t break unexpectedly. That’s not my style, though.

Starting from Day 11, the puzzles become more interesting. Some math or data structures are required to solve them.

- Day 11: The first part is plain simulation, but the second part can easily run the numbers out of range if you don’t manage them properly. Actually, modulo by the least common multiple of the divisors is a good way to keep them down.

- Day 14, 15 and 23: With a large coordinate space but limited elements, it’s a better idea to use a map or set instead of contiguous memory.

- Day 17 part 2: Running a simulation for 1000000000000 rounds is certainly not feasible, but it’s possible to find a pattern from the first 10000 or so rounds, and calculate the result from there.

- Day 18 part 2: Finding internal holes would be difficult, but flood filling from the outside is an alternative approach.

- Day 19 part 2: Even if searching for the “next robot to make” can’t keep the search space small, pruning near the leaves (i.e. stop searching in the last few minutes) can still cut it down by a large factor. This is the only way that I managed to bring the run time below 1 second.

- Day 20 part 2: Again simulating for so many 811589153 steps is not feasible, so like Day 11 part 2, it’s important to find a correct modulo.

- Day 21 part 2: At first this seems like tremendous work, but I made a bold assumption that the equation is linear (degree = 1), which turned out to be true. This enabled me to use very simple math to solve it.

- Day 22 is my favorite puzzle. Finding an algorithm to fold a flat layout into a cube is far from easy, so I hard-coded it for my input. (It seems like everyone is getting the same layout.) Such a two-layer

switchstatement is prone to bugs and took me the longest time to debug. - Day 25: To my surprise, the puzzle is missing a part 2. Maybe the author is getting on a vacation?

Finally, a magic trick that I discovered from Reddit for Day 15 part 2: Observing that the only uncovered space must be adjacent to multiple covered areas, examining the intersections of the edges of the beacons’ coverage areas produces a tiny search space. While it’s intuitive to build upon part 1’s solution, this discovery leads to a lightspeed solution.

Engineering the project

In fact, rushing to the puzzles was not even the first thing. I did not come across the event until my friend taoky recommended it to me. He was already halfway through the puzzles (his repository) and had set himself a set of rules, including one where “all solutions should take reasonable time and memory usage”. We discussed various methods to measure the time and memory usage, when he set it forth that it was not easy to add measurements to every single program.

Based on our discussion, I decided I would leave room for measurements when designing the project. So the first decision was to reuse code as much as possible within the project. For example, I’d like all solutions to share the same “peripherals” like the main function. This way if I want to add an extra feasure like performance measurement, I only need to do it once.

The next decision was to compile solutions for all puzzles into a single binary. Go is not known for producing small binaries due to static linking, so having separate binaries for each solutions implies a non-trivial amount of unnecessary disk space. Another reason is that due to Go’s package design, it’s more complex to selectively compile individual files than to compile all files together (the “package”). With a go.mod file present, go build conveniently compiles all files in the same directory.

With that in mind, here’s the first commit of the project. In addition to the code itself, two more design ideas can be seen:

- Individual solutions are in their own files, calling

RegisterSolutionin theirinitfunctions to register themselves. Also, the solution function takes a singleio.Readerinterface as input, so that providing input can be more flexible if needed. - If multiple input files are provided, the solution function sees a concatenation of all of them, similar to a number of common Unix tools. However, this little care was later decided to be unnecessary, and only a single input file would be processed.

Now with the project structure in place, I started working on the solutions. The second commit added my solution for Day 1 part 1, and it followed the designed structure like this:

package main

import ( ... )

func Solution1_1(r io.reader) { ... }

func init() {

RegisterSolution("1-1", Solution1_1)

}

While the first few days’ solutions were pretty ordinary, my design began to prosper when I started working on Day 5 part 2. The only difference between part 1 and part 2 is whether moving a stack of crates maintains or reverses their order. Compared to the common one-source-file-per-solution design, I can now reuse almost the whole function from part 1, and abstract the difference into a function parameter. This is how day5.go looks like after adding part 2:

package main

import ( ... )

func init() {

RegisterSolution("5-1", func(r io.Reader) { Solution5(r, Move5_1) })

RegisterSolution("5-2", func(r io.Reader) { Solution5(r, Move5_2) })

}

func Move5_1(...) { ... }

func Move5_2(...) { ... }

func Solution5(r io.Reader, moveFunc func(...)) { ... }

For Day 6, the benefit is even more prominent:

func init() {

RegisterSolution("6-1", func(r io.Reader) { Solution6(r, 4) })

RegisterSolution("6-2", func(r io.Reader) { Solution6(r, 14) })

}

Had I not designed the project this way, I would have to duplicate the whole function for part 2 only to change a single parameter, making things much more error-prone.

Adding measurements

Given the project design above, adding measurements is much simpler than it would have been if I had adopted the one-source-file-per-solution layout. It boils down to just two things:

-

A command-line flag to enable measurements:

flag.BoolVar(&fShowPerformance, "p", false, "show performance information") -

Adding

time.Now()andtime.Since()around the call to the solution function:start := time.Now() fn(r) duration := time.Since(startTime)… as well as displaying the result:

if fShowPerformance { fmt.Fprintf(os.Stderr, "\nDuration: %s\n", duration) }

Measuring memory usage is a bit more complicated. Go’s memory profiling doesn’t provide a simple “max usage in this session” metric, so I have to resort to OS-specific methods. On Linux, for the time being, I use getrusage(2) with RUSAGE_SELF, as two other known methods (using Cgroup and polling /proc/self/status) either require forking an extra process or add significant overhead and engineering complexity.

Now the program can produce a short summary of the performance when running a solution:

$ ./adventofcode -p 1-1 2022/inputs/1.txt

71780

Time: 875µs, Memory: 7.8 MiB

There’s one caveat here: The “Max RSS” value returned by getrsage(2) is the peak memory usage during the whole program’s lifetime, starting from when it’s forked from the parent process, when it inherits all mapped pages (resident set). Using an interactive Bash gives a minimum value of around 7.7 MiB, while using sh -c './adventofcode -p', adding a level indirection, reduces the starting size to 1.2 MiB.

Adding multi-year support

Up until now, the project has a flat layout with no subdirectories, and all Go source files start with package main. This is because I did not plan to support multiple years at the beginning. However, as I started working on puzzles from 2021, I realized that I need a better structure to support multiple years without worrying about namespace issues, like both years having a Solution1_1 function.

Moving each year’s solutions into a subdirectory is a natural choice. However, go build doesn’t pick up subdirectories by default, so I have to find a way to make it work. There are also some minor name searching issues, like RegisterSolution being defined in main.go but used in every solution file.

After a bit of trial-and-error, I carried out the following changes:

- Split out the “solution registry” into a

commonsubdirectory, making it a separate package that can be imported by each year’s package.- Each year’s package should import just

common.RegisterSolution, possibly wrapping it up to add a custom “year identifier” (this was implemented right after).

- Each year’s package should import just

- Move all solution files into a

2022subdirectory, and change the package name to justyear(because I don’t expect this directory to be imported and used with the package name). - Add

import _ "adventofcode/2022"inmain.gofor each year’s subdirectory.

In subsequent commits, I implemented “year selection” (e.g. choosing between the solutions 2021/1-1 and 2022/1-1) as well as more listings (e.g. ./adventofcode 2021/ to list all solutions for 2021).

With this in place, I can now add solutions for 2021 without worrying about name conflicts. For convenience, I also added auto-searching for input files in the current directory, so I can just run ./adventofcode 2021/1-1 to run the solution for Day 1 part 1 of 2021.

Epilogue

At this point, the project has successfully deviated from a collection of solutions to small-but-interesting puzzles, and has become more like a general-purpose tool for this kind of events. Nevertheless, it’s a fun journey as a software engineering practice, in addition to solving the puzzles themselves.

Looking at these paths I’ve taken, it is manifest that the initial decisions in the right direction are highly contributory in easing the development process, particularly when I’m coming back later to add a new global feature. This experience once again emphasizes the importance and advantages of having a clear idea of the project before starting to write code, as well as keeping the code in an extensible and maintainable fashion.

Leave a comment