Paper reading for [CIDR 2022] Are You Sure You Want to Use MMAP in Your Database Management System? by Crotty et al.

This paper highlights the problems with using MMAP in database management systems.

Background

MMAP is a POSIX system call that transparently maps file content to process memory (the virtual address space of a process). This allows programmers to simplify the logical structure of program by leveraging the OS page cache as a replacement for a manually-maintained buffer pool.

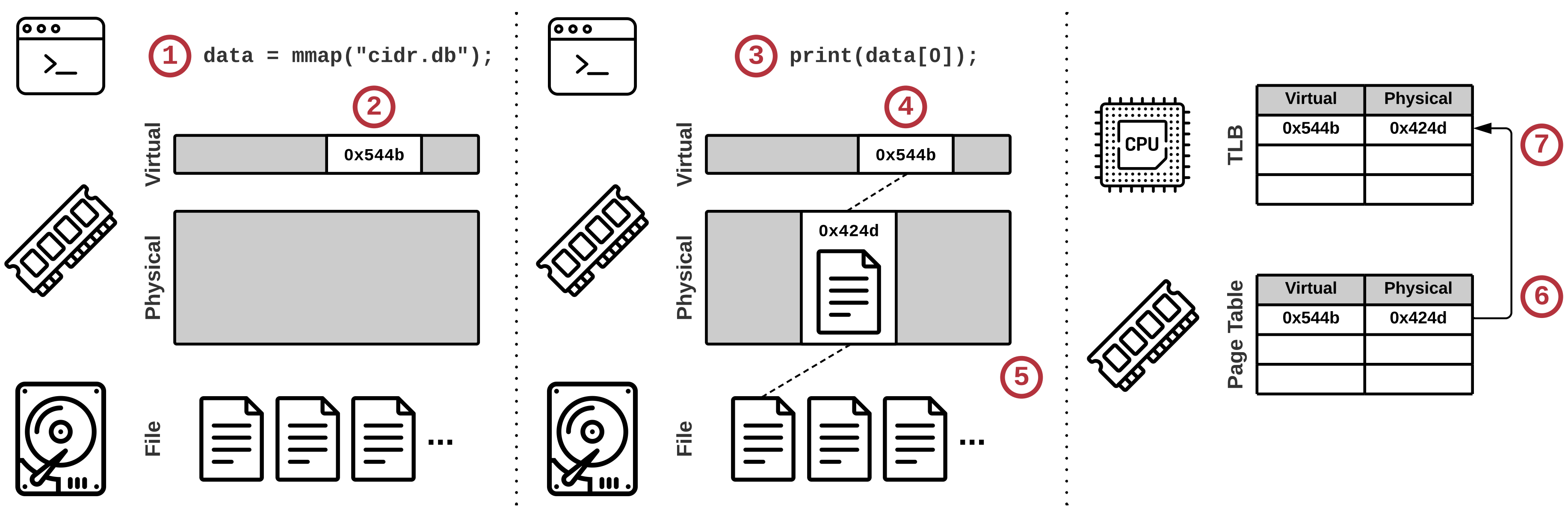

A typical MMAP procedure goes as follows:

- A process calls

mmap()for an open file. - The OS reserves part of the process’s virtual address space, but does not load the file from disk. The process receives a pointer to the mapped address.

- The process accesses the file using that pointer.

- The OS tries to load the page, but no valid mapping exists, which results in a page fault.

- The OS loads the file from disk to physical RAM.

- The OS adds an entry to the page table of the process, mapping the virtual address to the physical address.

- The initiating CPU caches this new page entry in its Translation Lookaside Buffer (TLB) for faster future accesses.

A process can map as much data from files as the virtual address space permits, and the OS does all the dirty work behind the scenes.

Files loaded this way count towards the OS page cache (shows in htop as both RES and SHR), so the OS must evict pages when physical memory fills up. During page eviction, the OS must ensure that:

- Dirty (modified) pages are written back to disk (if applicable).

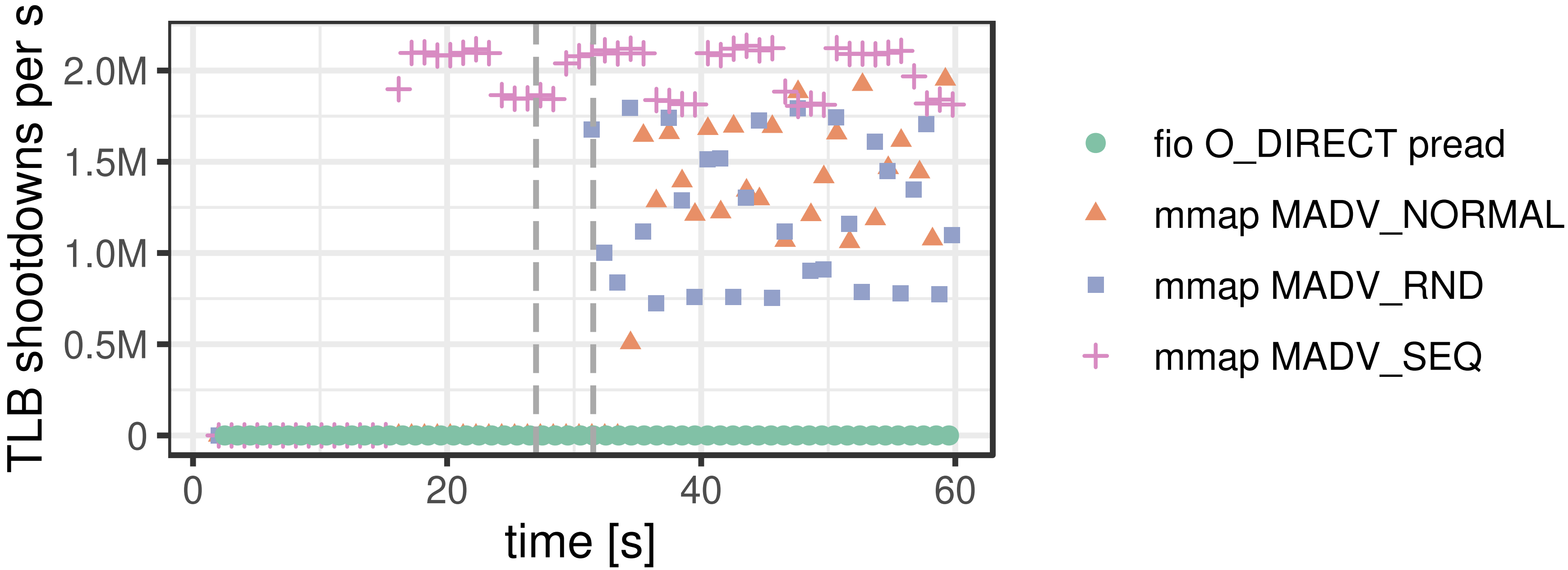

- TLBs of all CPU cores are flushed. This is called TLB shootdown.

Even though disk writes can be avoided on read-only workloads, TLB shootdowns are unavoidable. Worse, since modern CPUs do not provide TLB coherence, flushing TLBs is a costly operation.

Related POSIX APIs

mmap()maps a file to memory. TheMAP_SHAREDflag allows changes to be (eventually) persisted back to disk, while theMAP_PRIVATEflag indicates that modifications are discarded (private to the process). These flags cannot be changed after the mapping is created.madvise()provides hints to the OS about how the mapped file will be accessed.- With

MADV_NORMAL, (at least for Linux) loads 32 pages (128 KiB) for every page fault. - With

MADV_RANDOM, the OS only loads the exact missing page. - With

MADV_SEQUENTIAL, the OS loads more pages in advance.

- With

mlock()locks the mapped file in physical memory, preventing the OS from evicting it. It does not, however, prevent the OS from flushing dirty pages to disk.msync()flushes any modifications to the file back to disk.

Problems

Transactional safety

One important feature that DBMS provides is transactional safety, which is commonly referred to as the ACID properties. Using MMAP on database files poses a threat to theses properties, as OS can transparently flush dirty pages to disk at any time, which the DBMS is has no control over.

To work around this problem, the paper summarizes three kinds of approaches:

-

OS copy-on-write

The first approach maps the same file twice, one with

MAP_SHAREDand the other withMAP_PRIVATE. Any modification is first made to the private mapping, and then synchronized to the shared mapping. To maintain consistency, extra measures like a write-ahead log (WAL) are often used together.A noticeable problem with this approach is that as the database is being accessed, the DBMS will eventually end up with two full copies of the file in memory. While it’s possible to periodically shrink the private workspace, it adds extra complexity to the DBMS.

-

Userspace copy-on-write

The second approach is similar to the first, but instead of

mmap-ing the file twice, the “private workspace” is maintained manually as a separate buffer. This approach is more flexible in terms of memory efficiency and manageability. -

Shadow paging is a traditional copy-on-write technique. The DBMS keeps two copies of the database file, one for the current version and the other for the next version. When a transaction is committed, the DBMS simply swaps the files.

One downside is obvious: the DBMS must maintain two copies of the database file, which is not ideal for large databases. Even though it is possible to keep only the delta between the two versions, and only maintain the primary and shadow page tables, it introduces more fragmentation and requires careful bookkeeping.

Additionally, as commitments happens on the whole-file level, this method does not scale well with write concurrency.

I/O stalls

With traditional file I/O, the DBMS can use asynchronous I/O to avoid blocking the CPU.

However, with MMAP, as the OS evict pages in the background transparently, any access to the mapped file may block the thread. Despite having mlock(), it provides limited mitigation as the amount of locked pages is bounded. While madvise() helps with OS prefetching decisions, the control is still very coarse.

Last but not least, while it’s possible to spawn an extra background thread to prefetch pages, the added complexity defeats the purpose of using MMAP in the first place.

Error handling

For DBMS with page-level checksums (to prevent disk corruption), the DBMS must revalidate the checksums after every read, as it has no way to know whether the same page has been evicted and re-read from disk.

For DBMS written in memory-unsafe languages like C (which is quite common), a bad pointer write can silently corrupt the database. With a traditional buffer pool, defensive measures can be implemented to avoid writing corrupted data to disk.

Finally, with traditional read()/write(), error handling resides in the same place as the I/O code. With MMAP, however, error handling must be done through a cumbersome SIGBUS handler.

Performance issues

While it is a common sense that MMAP is more performant than traditional file I/O by eliminating the system calls and extra memory copies, experiments suggest otherwise. Three issues are pointed out:

- Page table contention (it’s one single data structure for the whole process)

- Single-threaded page eviction (Linux:

kswapd) - TLB shootdowns (see above)

Experimental results

Note on O_DIRECT

The FIO test uses the O_DIRECT flag to bypass the OS page cache. For a more detailed explanation, see this Stack Overflow question.

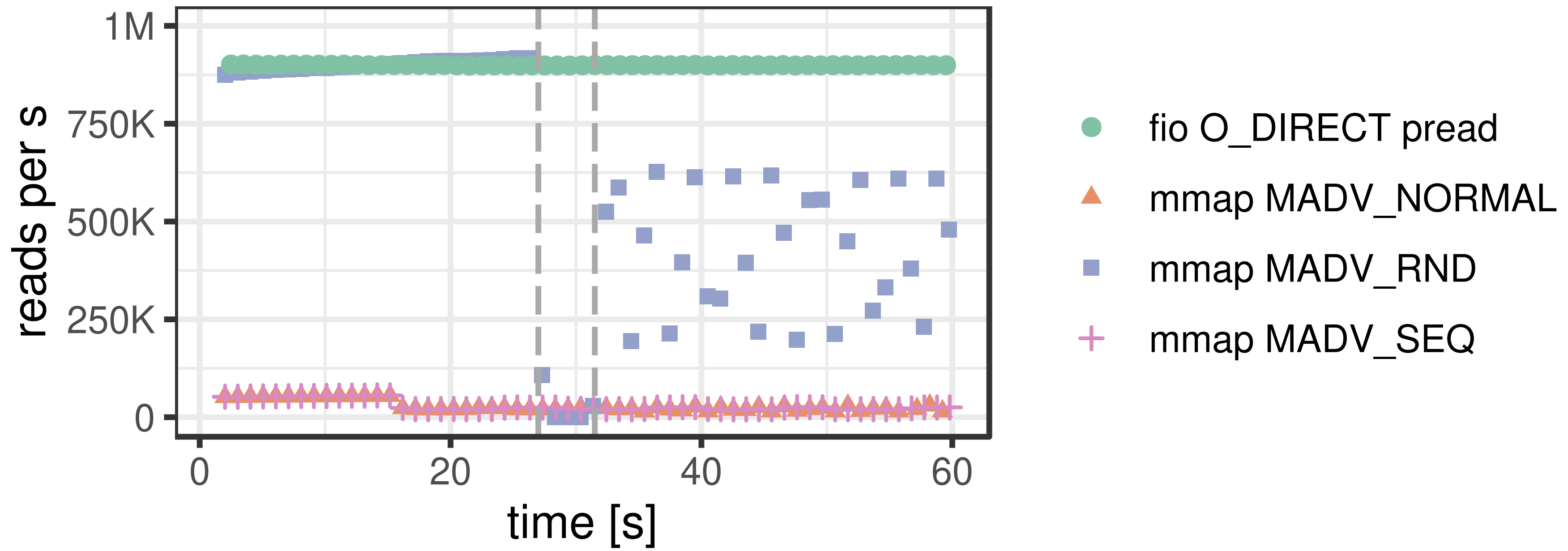

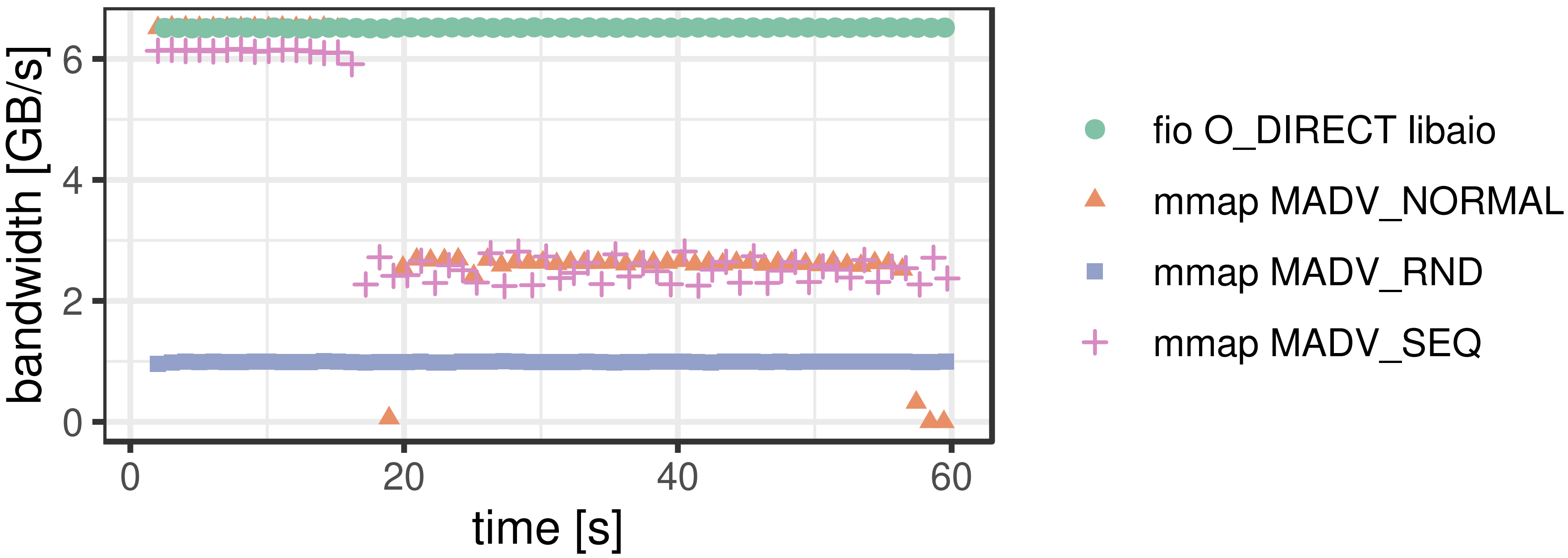

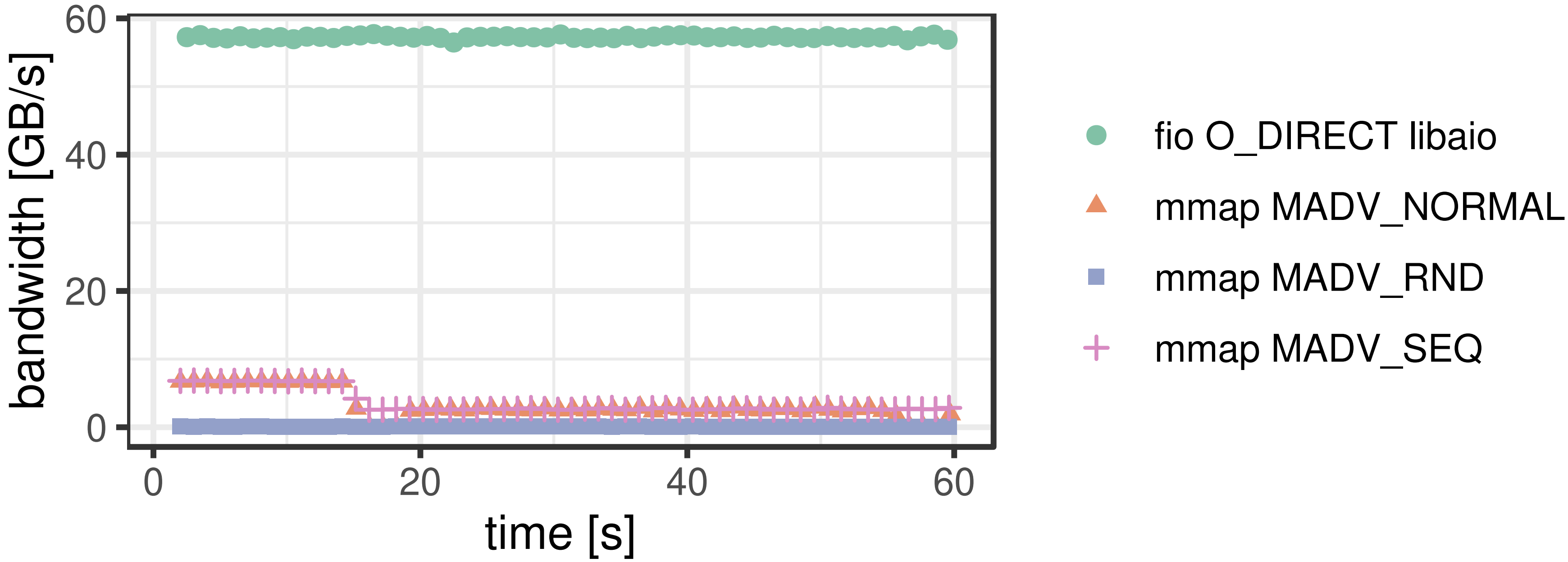

The paper presents two kinds of tasks: Random reading and sequential reading, to represent two typical kinds of database workload: OLTP and OLAP.

It is apparent that it doesn’t take long before MMAP can’t sustain its performance, which is due to the page cache filling up. The OS must work hard on evicting pages, which worsens the situation.

With sequential read, the performance gap is larger as disk bandwidth grows. While fio can almost saturate the bandwidth from 10 SSDs, MMAP’s performance stayed nearly the same. The authors attribute this to the single-threaded page eviction.

Conclusion

In the final section, the paper makes an ironic comment, suggesting two cases when you maybe can use MMAP in a database product:

- Your working set (or the entire database) fits in memory and the workload is read-only.

-

You need to rush a product to the market and do not care about data consistency or long-term engineering headaches.

Leave a comment